Introduction

The concept of using lasers to ignite propellant and energetic material is not new. At the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command-Armaments Center (DEVCOM-AC) at Picatinny Arsenal, NJ, the Army explored efforts to use external mounted lasers for medium- and large-caliber weapons systems, with modest success in the 1980s through 2010.

Early on, compact, solid-state, laser diode technology was an obvious solution but was in its infancy, costly, and an immature technology. Low‐cost, high‐volume production of microdiode laser manufacturing matured in the late 1980s, and the technology has continually been improving ever since.

Microlaser chips make it possible to fit the entire laser assembly into the munition itself as a onetime use, disposable component. This eliminates external optics, simplifies assembly, improves reliability, and avoids the problems associated with directing a laser beam through the gun breach. What makes microdiode laser ignition technology attractive is that it can be made seamlessly and interchangeably with existing electrically fired gun platforms without modification.

With advances in electronics and new threats from electronic warfare, the benefits of microdiode laser ignition are becoming clear. Older, established electrical ignition technology is susceptible to the ever‐increasing use of electromagnetic-radiation-producing devices (e.g., radar, directed energy weapons, etc.) on the battlefield. This is especially true on U.S. Navy ships that use high-powered radar near other onboard weapons systems. The effect of such radiation is known as Hazards of Electromagnetic Radiation on Ordnance (HERO), and its effect on a munition may require special procedures for munition handling. HERO testing of microdiode laser ignition devices has demonstrated these devices to be less susceptible or even immune for several reasons. The first is due to its inherent high (electrical) energy threshold required to produce the optical output (lasing action) required for ignition.

A second is that the electronics are physically isolated from the energetics so there is no accumulation of heat in the energetics. This is not the case for the established electrical ignition technology where the conducting media (heating element) is embedded within or is a part of the energetic material.

Work on applying surface mount, electronic manufacturing technology to 30-mm ammunition began in 2015 at the Fuze Development Center (FDC) at Picatinny Arsenal. The FDC is well suited for this task, as its mission is to transition research and development (R&D) prototypes to manufacturing and ultimately to the field. It also has a capability for state‐of‐the‐art surface mount technology (SMT) fabrication and assembly required for proving manufacturability in the private sector. The effort to use SMT on microdiode laser technology has been successful, leading to many government‐owned patents on the technology and a contract with two cartridge manufacturers to qualify the technology for 30-mm applications.

Today’s Electrically Initiated Devices

Most of the HERO issues are related to an electrical-based ignition technology developed in the early 1900s. A resistive-heating element generates heat to start the ignition process. This element is often referred to as a bridgewire or conductive mix, which, in some cases, is the energetic material itself.

This heating element is typically in close contact with the energetic material to maximize heat transfer to produce the fastest possible initiation time. This is particularly important in high-rate-of-fire applications ranging from 600 to 3,000 rounds per minute or higher. Prolonged exposure to electrical and/or radio frequency (RF) fields can create currents that may cause this resistive element to generate heat. Even when this current is not sufficient to initiate the embedded energetic material, long-term exposure to these fields (or heat in some cases) can chemically alter the nature of the energetic material, resulting in changes to the response times and/or sensitivity of these materials. This may damage the ammunition or increase ignition susceptibility, which could increase risk during ammunition handling. This problem is not limited to ammunition.

Other ordnance such as countermeasure flares used on fighter aircraft, cartridge/propellant-actuated devices (CADs/PADs), and detonators for explosives are also affected. Because bridgewire technology operates on heat generated from electrical resistance, Ohm’s law applies. This law dictates that the heat produced will be proportional to the current passing through the resistive element. A solution to the HERO problem is to find another way to transfer heat to the energetic material. Microdiode laser ignition can be a solution to these problems.

Why Microdiode Laser Primers?

The Navy is particularly interested in alternatives to conventional electrical ignition due to the potential susceptibility of electrically primed munitions to HERO aboard ship. While the prior work focused on 30-mm machine guns, recent activity is focusing on expanding the technology to include 20-mm platforms as well as other CAD/PAD systems. Personnel and helicopter electrostatic discharges (PESDs and HESDs) are also a concern. The HERO susceptibility problem has spread beyond Navy ships and now affects all services that handle munitions or explosives in all battlefield environments.

Microdiode laser ignition transfers heat in the form of infrared radiation. This can be done without making direct physical contact with the energetic material. Furthermore, lasers require a minimum energy barrier be exceeded before any coherent optical energy output can be produced and the resulting energy transferred to the energetics. This means that prolonged exposure to an electrical or RF field minimizes heat transfer to the energetic material if the munition is properly designed. The electrical current required for laser initiation is typically above 1 A or more, which is typically 2–3 times more than conventional, electrical ignition devices. It is also possible to further raise this current/energy threshold well above any possibility for unintended initiation in almost any HERO environment if the weapons platform can deliver enough current to the device to activate the laser.

The Past

In 2015, work began at Picatinny Arsenal to realize the concept of replacing the resistive bridgewire component of an electrically energized munition with a disposable microdiode laser. The 30-mm ammunition was the target application, as this ammunition is known to have HERO safety and PESD/HESD issues aboard Navy ships. There is also a strong incentive to explore and develop alternatives to solve this problem. Enough research had been done at that time to realize a microdiode laser primer could be made to seamlessly interchange with an existing 30-mm gun platform ammunition.

There were two immediate problems for adapting this technology into the existing primer cup. The first was soldering edge-emitting diodes on opposite sides of the chip, i.e., soldering top to bottom rather than a bottom-only surface, as in typical surface mount components. This problem is typically solved by wire bonding from the top surface to a bottom surface. A more robust, low-cost, mass-producible solution was desired for ammunition. This is largely due to the harsh shock, vibration, and temperature environment of the ammunition. It is also important to control cost for ammunition production. These rates can scale from thousands to millions of units per month.

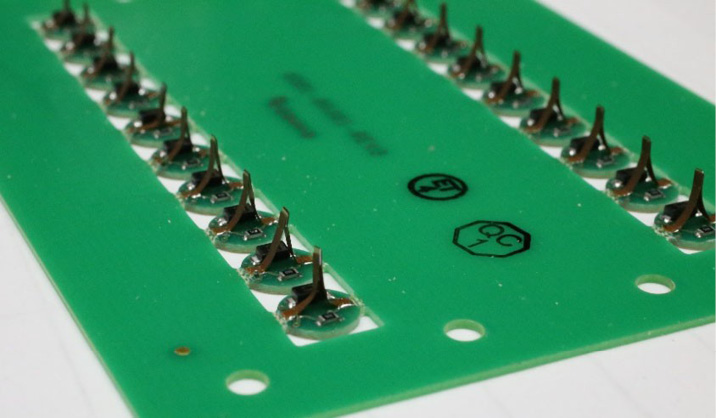

The second problem was adapting the edge-emitting laser to fire vertically into the 30-mm flash tube located above the primer. This is not possible if the laser is mounted horizontally on a printed circuit board (PCB). An answer to these problems was the flex mount technology, as illustrated in patent 9,618,307, “Disposable, Miniature Internal Optical Ignition Source for Ammunition Application” [1] (see Figures 1–3). The technology allowed the laser to be mounted so its output was directed vertically while being soldered to a horizontal surface. It also provided the ability to adapt the laser height vertically to minimize the air gap from the laser facet to the next assembly—the flash tube in the 30-mm case. This allowed the primer to be nonenergetic while the cartridge’s manufacturing and assembly were done by existing facilities with specialized safety protocols.

![Figure 1. Laser Flex Mount (Source: S. Redington et al. [1]).](https://dsiac.dtic.mil/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/redington-figure-1.png)

Figure 1. Laser Flex Mount (Source: S. Redington et al. [1]).

Figure 2. First SMT Laser Primers Assembled in 2017 (Source: S. Redington).

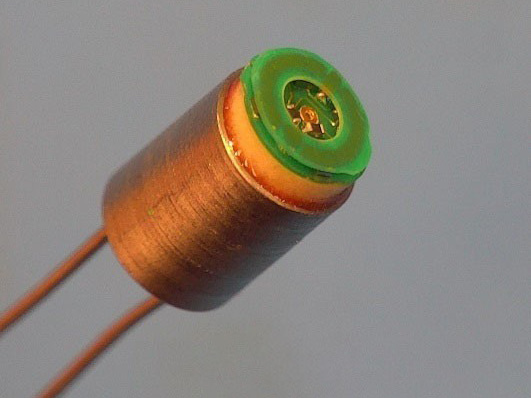

Figure 3. Nonpolarized Laser (Source: S. Redington).

A nonenergetic laser primer can be manufactured at any conventional contract manufacturing facility that can assemble SMT. In addition, a nonenergetic primer can be 100% tested before shipping to the cartridge assembly facility. This is not possible with existing bridgewire technology. As such, these two features were seen as benefits to the 30-mm application.

By 2017, the first functional microdiode lasers were produced on the FDC surface mount assembly line. This introduced a new generation of electronic primer with surface mount electronics embedded in place of energetic material. This capability also allowed more functionality to be incorporated in the basic primer itself. An internal continuity check and RF energy shunt features were added to the design. These early units were built up into PA520 primer cups (as shown in Figure 4), assembled into 30-mm cartridges, and successfully demonstrated as fully functional equivalents of existing 30-mm ammunition. It was later learned that such gun platforms were deployed with two differing electrical power configurations—one with the chassis connected to the positive terminal of the power source and another with the chassis connected to the negative terminal. The first primer design was a unipolar configuration. That meant there was no way to ensure operation on any fielded platform.

Figure 4. The First Microdiode Laser Primers (Source: S. Redington).

Because unipolar operation is an inherent property of all diodes, the laser diode is no exception. To eliminate this problem, the next generation design incorporated a full-wave rectifier, along with the continuity check and energy shunt features. The new design proved that more electronic functionality could be added to primer technology than just ignition alone. This gave way to the possibility of more advanced concepts like smart primers. These primers could embed memory, temperature sensors, and lock mechanisms that would enable security to be built into the ammunition itself. All these features were described in patent 10,415,942, “Disposable, Miniature Internal Optical Ignition Source,” granted in 2019 [2]. At that time, work began on applying the technology to 20-mm, electrically primed ammunition.

Extensive testing of the 30-mm laser primers revealed a weakness of microdiode laser primers. That weakness was with firing systems that utilize capacitive discharge as a means of energizing the primer. Unlike the target 30-mm firing platform, these systems have extremely low source impedance to maximize current through the primer. The target 30-mm platform has a built-in, 100-ohm impedance that limits the discharge current applied to the primer. Unfortunately, diodes do not handle unrestricted current flow very well or not at all. In the target’s case, the 100-ohm impedance restricts the current to a 1.5-A maximum. This works well for the laser diode selected for the 30-mm target application. Later experiments with capacitive discharge systems showed the discharge currents could reach 80 A or higher, albeit for an extremely brief period. Unlimited current tends to destroy the laser before it has a chance to output any laser energy. This presents a problem for advancing the technology beyond the target 30-mm application.

The Present

An important design consideration for a microdiode laser primer is that the microdiode laser acts like a one‐time, single-use electrical fuse. In that respect, traditional design for reliability does not apply. For example, lasting thermal effects that would otherwise prohibit use of a laser diode can be totally ignored. As a result, bulky heat sink mechanisms are not required for a laser primer to perform its one‐time function. This simplifies the design and allows a greater potential for microminiaturization.

The design requirement to consider is that the diode performs its mission before it self‐destructs. This is relatively easy to do for a power source with a built‐in impedance and has been demonstrated on the Apache platform. Ignition was achieved in the first versions of laser primers, with less than one millijoule of input energy in less than 100 µs. Uncontrolled impedance sources present a very different circumstance due to their high-current, short-duration pulse. The problem is that the diode fails before the device can deliver useable laser energy or the pulse is so short that there is not enough time to achieve ignition. In this case, reliability is a race against time.

Work began late in 2019 to develop a new circuit concept to adapt the technology to the capacitive discharge supplies. The challenge for smaller-caliber applications like the 20 mm is that there is no flash tube in the cartridge. Flash tubes are required in larger-caliber munitions to boost the propellant ignition point deeper into the center of the cartridge rather than lighting the propellent from one end. This greatly reduces the time to burn all the propellent. The 30-mm flash tube allows the primer to be completely inert since all the ignition requirements can be met by a flash tube modified to accept the laser input. This combination makes up for the lost energetic material in the PA520 primers used in producing 30-mm ammunition. This is not possible when there is no flash tube, as in the case of small-caliber ammunition.

The primer itself must contain sufficient energetic material to boost the ignition output fast enough to completely ignite the propellant. This reaction time is a factor that must be considered since this must be done within the time required to fire the next bullet. Replacing the bridgewire with electronics severely limits the available space if that space needs to be shared with energetic material to meet performance requirements. Firing the laser vertically into an adjacent flash tube is out of the question for small-caliber applications since there is no flash tube.

These new problems led to the concept and development of radially fired laser technology. The benefit of the radially fired design is that energetic material can be contained in a center cavity at the bottom of the primer. This material is initiated from the side as opposed to above. This creates space in the primer cup for energetic material lost in the flex mount design. The energetic material can also be completely isolated from the electronics’ direct contact by encapsulating the circuit assembly in an optically clear epoxy.

The first radially fired laser was developed late in 2019 and is shown in Figure 5. A second, more-refined version is shown on the right and was produced later that year. The primary difference was a castellated solder joint for soldering the PCB to the primer cup side walls rather than the unsupported solder joint of the original design. This new design incorporated a high level of integration in a smaller space than previous designs. Not only was the full wave bridge rectifier and continuity check incorporated, but a load bank and transient voltage suppressor were added to dissipate the excess energy of a capacitive discharge supply. This design was created to function in 30- and 20-mm applications. The radially fired laser was successfully demonstrated and patented in 2022.

Figure 5. Radially Fired Laser (Source: S. Redington).

A problem with capacitive discharge firing supplies is the amount of excess energy they deliver. This energy must be dissipated to protect the laser long enough to successfully ignite the energetic material. To complicate matters, the amount of this excess energy depends on the specific gun platform in use. Testing of the latest version indicates the design is compatible with the target 30-mm platform, along with capacitive discharge energy levels typical of older, existing platforms.

The complication of evaluating the design for all platforms lies in the stored potential energy of the firing circuit. Given that the current of the discharge is unlimited by any significant series resistance, the total energy that must be handled by the laser primer is given by the formula 1/2 × 𝐶 × 𝑉2. Both the capacitance (𝐶) and voltage (𝑉) depend on the specific gun platform. The challenge is that the energy is proportional to the square of the voltage.

Testing done on the 2022 design indicated it was likely to work for many capacitive discharge supplies currently fielded; however, there are exceptions. When a developmental 20-mm platform was studied, it was found that the firing voltage could reach as high as 315 V, with 3 µF of capacitance (149 mJ). This is an unprecedented energy level and one that the 2022 design is unable to handle. The underlying problem is dissipating that much excess energy in such a small, confined space.

It should be noted that a 250-V, 3-µF capacitance energy level (95 mJ) was successfully demonstrated. This indicates a solution is possible. Clearly, understanding the firing circuit issues and challenges has dramatically improved from the early designs. More investment is needed to develop a general design capable of being quickly adapted to function in the myriad of capacitive discharge firing circuits in existing platforms.

The Future

Enough R&D has been performed to show microdiode laser ignition has a future in applications where HERO, PESD, and HESD safety are a concern. The technology directly applies to electrically primed, small- and medium-caliber ammunition and artillery. There is also potential to improve testability and reliability in critical applications such as countermeasure flares, squibs, and CAD/PAD applications (see Figure 6). Placing electronics in the primer cup can also enable smart ammunition. These are munitions that could use one‐wire technology to communicate to the platform or user for information or control. Beyond that, applications like HERO safe replacements for electrically initiated detonators are possible.

Figure 6. Microminiaturized Bipolar Laser (Source: S. Redington).

Laser ignition has been shown to work in an M6 blasting cap, demonstrating potential applications in demolitions. This would also suggest an M100 detonator replacement is possible. Many of these applications require a continued investment to adapt the technology to capacitive-discharge-type firing power supplies. The challenge is to adapt the discharge current to match the laser diode’s capability. This must be done in the smallest amount of space with two aspects: (1) hold off a large amount of excess energy and stretch it out over time and (2) do this in an extremely small volume.

A practical goal for the future is a common basic design that would be suitable for as many applications as possible. A design that can handle capacitive-discharge-type firing supplies is key but not a limiting factor.

Fuzing is a potential application where the electronics design can adapt to the laser technology. This is because each fuze application functions as its own, self‐contained system. Backward compatibility with an existing weapons platform is not an issue in this case. As such, the impedance source can be made to match the laser diode; capacitive discharge is not an issue. This would also be true of new, emerging applications. This means that despite the problems encountered with capacitive power sources, the future of laser primer technology is still promising.

Getting Microdiode Laser Technology to the Field

Backwards compatibility with existing platforms is a requirement for any new electric primer technology. In virtually every case, retrofitting existing platforms would be extraordinarily expensive and highly undesirable. In addition, any solution that prevents the prior technology from being used would not be practical or accepted. Continued R&D must be explored for microdiode laser ignition to become a viable, cost‐effective alternative to current electrical-based ignition devices. For example, in the high rate of fire for 20-mm ammunition applications, this technology necessitates a high volume/low‐cost end item to be a realistic alternative to existing technology. A major cost driver of this technology is the cost of the laser diode.

Studies show that it is possible to mass produce such laser diodes within an acceptable price point to be practical for the mass production rates of most ammunition. This is proven by the low cost of diode laser devices used in compact disc players, laser pointers, and automotive light detection and ranging. These low‐cost laser diodes are readily available from suppliers in Asia. Unfortunately, the United States no longer possesses a manufacturing capability for low-cost, laser diode technology, as the offshore availability of these lasers is plentiful. There is currently no market influence in this country to increase production or reduce cost for onshore production.

The COVID pandemic has exposed the United States’ dependence on foreign technology for military and commercial markets. This is particularly troublesome for military markets, as tensions rise with China. The U.S. government has recognized the problem and responded with the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, which supports domestic production of semiconductors.

Regardless of the supply chain issue, increasing demand for diode lasers is essential for lowering manufacturing cost. Military applications would tend to demand a domestic supply be developed. Such application areas could be initiating devices used in artillery, demolition, or CAD/PAD devices, as well as similar devices within the commercial sector like automotive air bags, fire extinguishers, or mining.

One application explored was a potential primer M123 replacement used in artillery. Another was a laser-initiated M6 blasting cap. Both applications showed potential for the technology. Use in countermeasure flares and CAD/PAD devices was also explored briefly. Enough development was done to show promise; however, a primer that can work with capacitive discharge firing systems is required for many of these applications.

Conclusions

In summary, microdiode laser technology has a lot to offer across a span of multiple platforms. Low‐cost, high‐volume production is possible for military and commercial applications. There are many new applications that could be enabled by this technology, such as smart ammunition, nonenergetic tracers, time-delayed functions, and more. The technology also has the potential to solve manufacturing and reliability issues with current bridgewire technology that tends to be fragile in harsh environments.

Perhaps the most appealing aspect of laser ignition is its ability to provide immunity from HERO effects in the modern battlefield. This is certainly a concern with munitions aboard Naval ships employing high-power radar. This is also a problem that concerns fire-suppression and pilot-ejector systems aboard military aircraft. In the end, the path forward for laser ignition relies on finding the right application, engineers with imagination, and those willing to invest in the technology.

References

- Redington, S., C. Macrae, G. Burke, and J. Hirlinger. “Disposable, Miniature Internal Optical Ignition Source for Ammunition Application.” U.S. Patent 9,618,307, 11 April 2017.

- Redington, S., G. Burke, and J. Hirlinger. “Disposable, Miniature Internal Optical Ignition Source.” U.S. Patent 10,415,942, 17 September 2019.

Biographies

Stephen Redington, PE, is a senior engineer at DEVCOM‐AC, with over 30 years of experience in leading-edge hardware design and development for the military, aerospace, and telecommunications industries. His engineering experience ranges from design conception to product manufacturing in military and private sectors. He has made several innovative advancements in inertial guidance, Global Positioning System, and telecommunications technologies. He holds multiple patents regarding laser ignition and explosives safety, including a patent on vertical soldering for three-dimensional circuit assembly. Mr. Redington holds a B.S. in engineering from Rochester Institute of Technology and a graduate certificate in object-oriented design from New Jersey Institute of Technology.

Gregory Burke is a recognized subject matter expert at DEVCOM‐AC in high-power laser systems for directed energy, ignition of energetics, and biomedical technologies. He has supported the laser ignition program for the U.S. Army’s LW-155 howitzer program as well as the Crusader program. He served as president and principal investigator for Aurora Optics, Inc., where he worked on several contracts with the U.S. Army, Navy, and National Institutes of Health. He holds multiple patents in laser technology, microwave-based medical diagnostics, and other applications merging optics, electronics, and mechanical systems. Mr. Burke holds a B.S. in environmental engineering from Ramapo College.